Stanley Stewart

In the helicopter, banking above the dry grasslands of Moremi, we passed a flying spider. I glanced out the window and there it was, happily sailing along on gossamer threads, legs stretched out, belly up as if it was lying in a hammock. I wondered if Africa had gone to my head, if life here had become so odd, so wild and so fanciful, that I was imagining things. The whole place was starting to feel like la-la land.

On the dirt air strip, where the safari jeep was waiting to take us deeper into the bush, I mentioned the spider, tentatively, to the pilot. “Yup,” he shrugged. “Spiders fly. Welcome to Africa, home to the weird and the wonderful.”

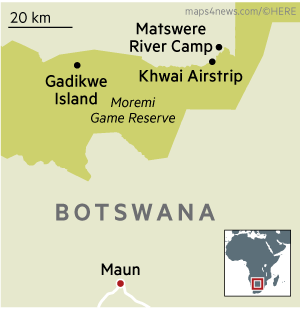

I had come to Botswana, to the fringes of the Okavango Delta, to meet a new generation of safari guides. I wanted to avoid lodges with spas and room service, with air conditioning and fusion chefs, with pillow menus and interior design stylists, all those unnecessary luxuries that cocoon visitors from the Africa they have come to experience. I wanted to be closer to the African earth. Barclay Stenner Safaris, run by two boyish chaps in their early thirties, have gone back to basics, to an African experience where the wraparound sound systems are the sounds of the African bush. Its safaris can legitimately be classed as luxury, but the luxury is of a different sort.

travelling by boat through the Okavango Delta. Main image above: Matswere River Camp

John Barclay and James Stenner are not hoteliers, they are safari guides. Their passion is Africa, not entries in The World of Interiors. Sybarites fear not; there is no question of roughing it. You have everything you need — excellent food, good wines, comfortable tents, hot showers, flush loos, old-fashioned camp furnishings, all executed with style and charm — but nothing you don’t. The luxury is about the experience, not the duvets from Milan. It is also about the level of personal service. John and James themselves lead their safaris, which are private, exclusive to each client, and tailored to their interests and inclinations. Though they stay two or three days in one camp, the point is to be nomadic — “as mobile as the game,” John says — so that their safaris will typically feature two or three locations. They want more than a checklist of the Big Five. They want a sense of exploration. They want to take guests on a journey, and send them home with a sense of wonder.

The two men come from contrasting backgrounds. James dreamt of Africa as a child, consuming National Geographic magazines and natural history television programmes in distant Northumberland. His own African adventure began when he fortuitously landed a job as a manager at a safari lodge. By contrast, John is a sixth-generation African safari guide, born and bred on the continent, a descendent of Richard Granville Nicholson, the explorer, who led Cecil Rhodes into what is now Zimbabwe. His grandfather was Jack Bousfield, adventurer, safari guide and famous hunter turned conservationist. His uncle is Ralph Bousfield, yet another celebrated guide, who set up Jack’s Camp in the heart of the Kalahari. John learnt his trade at his uncle’s knee, and he does him great credit.

A leopard spotted in the bushes

Our first camp — Matswere River Camp — lay on the banks of a small lake. Lanterns glowed among the trees. James was serving cocktails, hot water bottles were being ferried to our tents, the table was laid for dinner — white linen and silverware — and all was well. We sat round the camp fire, nursing drinks and swapping stories.

I mentioned my spider. Parachute spiders, John said. He explained that they launch themselves from the tops of trees, spinning out thread in a triangular parachute to carry them on updrifts of wind. While most flights are measured in metres, some last miles. Sailors have reported them caught in their sails almost 1,000 miles from land.

Conversation turned to other improbable insects. There was the armoured ground cricket, the Bill Cosby of the insect world, which drugs females before mating with them. There was the beetle in the dry Kalahari that stands on its head overnight to allow the droplets of morning dew to run down its back into its mouth. There were the termites, so numerous that if you balanced them against all the other creatures in the Okavango, they would outweigh them by four to one. And of course there was the praying mantis; the female famously eats her mate during copulation so that males have evolved to continue mating, and delivering their sperm, even while their partners have chewed their way through their heads.

Later in my tent, I lay listening to the chorus of reed frogs that filled the night. Barely the size of a fingernail, the males wrestle one another to get to the top of the slender water reeds that surround the lake. From their perch, they sing to attract a mate, an individual note repeated. But each frog’s note is different, so that together dozens of reed frogs sound like a chilled xylophone player, out there in the darkness, playing a piece of cool modern jazz — meandering notes and soft tinkling patterns. Deep in the Botswana bush, the lullaby of the amorous reed frogs sang me to sleep.

In the early morning, we set off with the shadows of the mopane trees stretched across the grasslands. Clouds rose like loaves around the horizons. On the edge of a wood we found a pair of wattled cranes. Standing over 5ft tall, they are the antidote to the ruthless mantis. Every morning the male dances for his mate, spreading his wings, bobbing his head, prancing back and forth like an avian Mick Jagger. Wattled cranes mate for life; the pair we saw might already have been together for 10 years. But every morning, he liked to show her those moves, sweetly, elaborately, maybe a little over enthusiastically, to remind her why she had chosen him in the first place.

Round every bend in the track we seemed to encounter another bull elephant, calm, solitary, colossal, survivors from the distant age of megafauna. John was explaining about their communication. They “speak”, often using their trunks, at a frequency too low to be audible by the human ear. And they can “listen” by picking up sound vibrations from the ground through aural pads on their feet. Researchers have been able to identify 30 different vocalisations, which can be communicated over miles.

At an al fresco breakfast stop, we watched open-billed storks sailing around skeletal trees, herds of lechwe antelope scattered across the plain, suddenly raising their heads as one, and a single male wildebeest waiting forlornly beneath a tree for a passing female. Later that morning we came upon a leopard which strolled so close to our jeep — barely a metre away — that we could smell her, that strong feline scent. She marked a fallen log, spraying it, then paused, gazing up at a tree, looking for guinea fowl for breakfast. The next day we would see her again, with something more than guinea fowl. We found her under a tree, her whiskers bloodied, as she hunkered over a waterbuck kill.

Two days later we headed into the Delta, travelling by boat across the Xakanaka Lagoon into the Maunachira channel, between wide reed beds. In this watery labyrinth of winding channels and sudden lakes, it seemed the world was still emerging from the Flood, fluid, newborn, teetering between earth and water. The reflections of clouds glided down the channels.

Elephants swam across a lake, their trunks raised above the water like snorkels. Tiny malachite kingfishers glinted among the reeds like jewels. Beneath us, underwater gardens undulated in watery slow motion. Beyond a bed of papyrus we spotted a sitatunga, the mysterious aquatic antelope.

At dusk we landed on an island of strangler figs, far out into the Delta, stepping ashore into a remote fairytale world. Our camp awaited beneath colossal mangosteen trees, a species first described by Livingstone. A lane of lanterns led to the campfire and the table set for dinner. The aroma of roast lamb wafted from the kitchen tent. After warm bucket showers, drinks were served as we gazed upwards between the boughs of the trees at stars thick as grapes.

River bushmen — the Ba Yai — traditionally live on these admirable Okavango islands. Everything they need is here — game and fish and edible leaves, wild basil to cure coughs, the soft flowers of the Kapok bush to fill their pillows, shepherds’ bush whose roots could be ground into flour, sage leaves as an insect repellent, plus a very useful caterpillar that can be slipped into a husband’s stew to induce a fatal heart attack.

A bull elephant

After dinner we pushed out on the lake in a piroque. The eyes of crocodiles glowed in the light of our torches and the stars trembled in the mirror black of the water. Later I slept as if drugged and dreamt of swimming with elephants. In the morning I was woken by a scops owl, the alarm clock of the Okavango, ringing like a telephone, briiing, briiing.

Africa seeps into you, inscribing its indelible memories. But it is not just about the wonderful and the miraculous, the unbelievable things you learn every day. Sometimes it is just the details — the taste, the smell, the feeling of the country, some personal safari of sensations, all strangely moving in this place where we are tempted to feel a kind of kinship, a sense of home.

I remember the sounds of the night, a bull elephant trumpeting somewhere in the grasslands, hippos grunting from the shallows, a hyena whooping close by. I remember the eerie saw-like sound of the leopards in the dark, as if they were snoring, and the giant eagle owls muttering, as if they were dreaming. I will never forget the tinkling music of the reed frogs, singing for love.

I remember the early mornings, the fire glowing in the pre-dawn at the centre of the circle of camp chairs, the smell of coffee as the day began to lighten and the grey trees materialising out of the dark. I remember the extraordinary stillness of those mornings, without a breath of wind, as if the world had paused for a moment, waiting, for the day, for the rising sun, for the animals. Later when we set off in the safari jeep, with the chill of the night still with us, it was the sheer delicacy of the light across the grasslands. And in the evenings coming home, it was the long splayed shadows of the mopane trees, and the intoxicating scent of sage, filling the evening.

There was the bull elephant who paused at his breakfast to focus one great eye on us, contemplating from beneath those long lashes, our gaze connected for a moment in some silent exchange. There were the martial eagles, soaring magnificently far above on wing spans well over 6ft, birds who could see for miles in minute and precise detail, like gods. I remember the regal disdain of our leopard. And the haunting beauty of her kill — that dead waterbuck.

The leopard was crouched over its midriff, already gaping open, a mess of blood and entrails. But it was the waterbuck’s head I remembered. It looked as if it could be asleep, peacefully lying there, on a pillow of grass. Dead only an hour or so, it was still untouched and perfect. So it would probably remain, until the vultures came.

Botswana is one of the greatest wildlife destinations on the planet. It may be a place of endless wonders, of a hundred things a day that are barely credible. But it is not really la-la land. It is a place where real raw life comes at you with head-turning speed, the whole full-on drama — birth and death, tenderness and violence, and luck, good and bad. Our leopard got lucky. The waterbuck didn’t.